Simon Burgess and Rebecca Allen

Much of the media comment on today’s National Audit Office’s (NAO) report on academies has rightly focussed on issues of governance and financial management. In this post, we dig a little deeper into some of the other claims in the report. We are less optimistic than the NAO – less optimistic that the academy programme has had a direct impact on the improvement of deprived and very poorly performing schools; and less optimistic that these schools are no longer avoided by the middle class.

Are academies outperforming comparator schools?

One key issue is whether academies are outperforming other comparator schools. This question – and the possible answers – illustrates the fundamental problem in policy evaluation. It is never possible to truly observe what would have happened in the absence of the policy. In this case, if a school became an academy it is simply not possible to know for sure what would have happened to it if it had remained as a community school. So researchers have to make assumptions to produce estimates of the effect of the policy. One way is to look at what happened to close comparator schools and to assume that something similar would have happened to the academy: for obvious reasons, this is called matching.

The NAO analyse the GCSE results for the 62 academies that have at least two years of post-opening exam results available. They do this by matching the academies to a set of non-academy schools that have a similar demographic profile in their pupil intake. If we take the widely used indicator of the proportion of pupils gaining five or more A*-C grades at GCSE (including English and maths) academies do indeed appear to have achieved slightly higher growth in this headline statistic than matched non-academies; this is clear in Figure 8, page 19 of the main report.

This analysis answers one specific question – have the results of these schools grown more or less quickly than schools with similar levels of deprivation. This is clearly an interesting question, but it may not be the right question. We need to remember that the original intention of the academy programme was to act as a tool to turn around failing schools. So the early academies were necessarily very poorly performing schools. The right question to ask is whether becoming an academy as part of this programme helped this growth: whether, to use the technical language, there was a causal impact of academy status on exam grades.

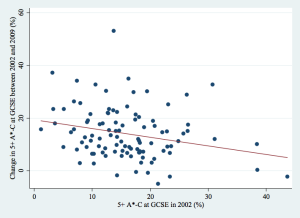

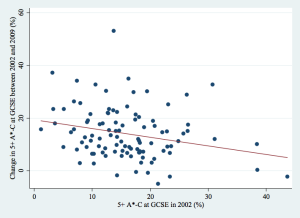

The issue is that the schools chosen to become academies early on were very poorly performing schools. For many such schools, the only way to go is up. In other words, a lot of the poorest performing schools would have improved anyway, regardless of academy status. We can see that easily in Figure 1. This shows the improvement in GCSE performance from 2002 to 2009 of schools in the lowest 5% of the ability intake (and by extension, the most deprived schools) and excludes all academies. This Figure suggests that “reversion to the mean” is an important component of the recovery of all poorly performing schools, and we should be cautious in assigning all of that recovery to the academy programme.

NAO show that, having underperformed similarly deprived schools in the early years of data, by 2009 they have indeed caught up and are no different in their performance on the metric of five or more A* to C grades, including English and maths. However, it is worth noting that academies are outperforming schools with a similar demographic profile on the old-style measure of the proportion of pupils achieving five or more A* to C grades, excluding English and maths. This suggests academies have been focusing on non-core subjects and NAO note that they are making greater use of vocational qualifications to boost their results than other schools. Michael Gove should therefore bear in mind that downgrading the equivalencies of vocational subjects might substantially change the perceived success of the academies programme.

Are academies becoming less deprived? And is this good or bad?

The second important point made in the report is that the academies programme is becoming substantially less deprived over time. Almost all of this change in the overall average is because succeeding generations of academies have been less deprived, rather than any individual cohort of academies filling up with less deprived children.

But we would go a little further than this. Much of the small decline in the percentage of free school meals eligible (FSM) students within a cohort of academies will be accounted for by the general growth in the economy over that period. The percentage of FSM students was declining in all schools over this time, so nothing special was happening in academies.

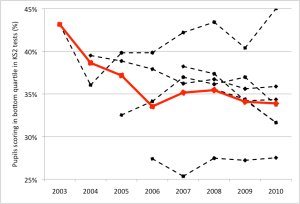

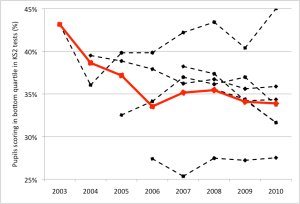

In order to shed a little more light on this, we look at another indicator of school composition: we use some of our own schools data on the proportion of pupils who scored in the bottom quartile in the Key Stage two tests at the end of primary school. This is not susceptible to the economic cycle. In the average secondary school, 25% of pupils will have scored in the bottom quartile but academies are more deprived than the typical school so this figure is usually much higher.

Figure 2 shows that the proportion of low ability pupils in year 7 (age 11) cohorts has indeed fallen from a very high figure of 43% in 2002/3 to 34% in 2009/10 – this is the red line. However, any particular cohort of Academies does not appear to follow a pattern of increasing or decreasing ability profile of pupil intakes. For example, the first 2002/3 cohort had 43% low ability pupils in its first year versus 45% in the latest available year of data. Only the 2006/7 and 2007/8 cohorts appear to have improved their ability profile slightly, but both are still substantially more deprived than the typical school.

One perspective on the (un)changing demographic profile of academies is that this is a success: these well-resourced and high-profile schools have not been colonised and taken over by the middle class, elbowing the poorer students out. But another perspective is that these schools remain far more deprived than average, and an increase in the fraction of more affluent students would be beneficial to students and to the school. It appears that neither of these things has occurred – the intakes remain about the same on average as when the schools joined the programme, and the typical academy does not appear to have experienced a substantial new influx of middle class students.