Rebecca Allen and Simon Burgess

From next week, officials in the Department for Education are going to be busy sifting through responses to the consultation exercise around the new School Admissions Code.

Two important issues in the proposed code relate to the priority given to school staff, and to random allocation. We believe that as they currently stand, these provisions will set back the goals that the Government has set for its education policy.

1. Prioritising the children of staff

Paragraph 1.33 of the code says: “If admissions authorities decide to give priority to children of staff, they must set out clearly in their admission arrangements how they will define staff and on what basis children will be prioritised.”

This suggests that admissions authorities are to be allowed to prioritise the children of staff, reversing the policy of recent Admissions Codes.

One group very likely to be included in most definitions of “staff” are teachers. For those teachers with children, this will add a new aspect to their decision on which school to seek a job at. Like many other parents, teachers will be keen for their children to attend high-performing schools.

Following the White Paper “The Importance of Teaching”, one of the leading education policy issues is how to attract the particularly effective teachers into the more challenging schools. Research evidence does not tell us whether teachers who are parents are on average more effective teachers, but there are two points to make:

- This policy change will differentially increase the flow of applicants to high-performing schools. If the Headteachers of those schools are skilled at spotting effective teachers, then simply having access to a much bigger applicant pool will raise the average effectiveness of teachers the hired at those schools.

- They are less likely to be novices, which is one of the few clear findings on teacher effectiveness, so in that sense alone teachers who are parents are likely to be more effective.

Given that, this policy change is very likely to work against any efforts to attract effective teachers to challenging schools, and thus set back the Government’s stated educational policy goals of narrowing the outcome gap between affluent and disadvantaged pupils.

The proposed code change will also complicate disciplinary procedures because firing a teacher from a school would also have implications for her/his children. This is likely to make it even less likely that headteachers will engage in robust performance management.

We know that any work-based privileges that are specific to particular establishments tend to cement people in that job and reduce turnover. Such privileges include health insurance, pension rights, and so on. This reduces labour mobility and typically will make the labour market less efficient. This proposed change will have the same effect in the teacher labour market as teachers will be less willing to move as it will disrupt their children’s education.

The core issue is where the most effective school staff work. It would clearly be in high-performing schools’ interests to define staff quite widely to attract highly motivated and effective governors and other staff. School leadership is key to excellent schools, ever more so as more schools become autonomous. If the children of governors were also prioritised for admission, then we would likely see an improvement in the quality of governors at high-performing schools and a decline at more challenging schools.

These points are about the effectiveness and efficiency of schools. There is also a fairness point about equity of access to high-performing schools. Some schools might define “staff” quite widely to include Teaching Assistants, lunchtime supervisors, and governors as well as teachers. In such cases, becoming one of those staff is an attractive route of access into the school, as an alternative to buying a nearby house. In extreme circumstances, individuals could offer to work for free as lunchtime supervisors, or could offer to provide goods or services to the school to become governors. While many may apply for such positions, schools will naturally choose the more able and articulate applicants, particularly those with a professional background. This will not help to foster more equal access to high-performing schools.

It may be that the provision to allow this prioritisation of staff was a way of finessing the problem of how to guarantee that the founders of free schools can get their children into ‘their’ school. If so, it might solve a problem affecting possibly 5% of pupils at the cost of the problems outlined here for the rest.

2. Random allocation

Paragraph 1.28 says “Local authorities must not use random allocation as the principal oversubscription criterion for allocating places at all the schools in the area for which they are the admission authority.”

This paragraph bans the use of lotteries as the main mechanism for resolving over-subscription across an LA. The problem of who is admitted to the high-performing over-subscribed schools is highly relevant to the Government’s goal of closing the outcome gaps between affluent and disadvantaged pupils.

The Government has stated that the primary goal of its social policy is to raise social mobility. One of the central ways in which where you were born influences your life chances is through the assignment of children to schools, governed by the Admissions Code.

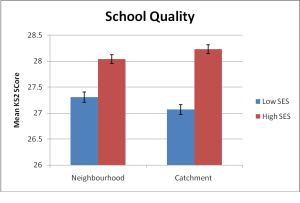

Currently, the main mechanism to resolve over-subscription is proximity. It is clear that the widespread use of the proximity rule widens the socio-economic gap in the available quality of schooling. In fact, the gap in accessible school quality between rich and poor families widens by over 50% once a proximity criterion is imposed.

We can illustrate this straightforwardly, using data from the annual Census of all state school pupils in England. We can approximate the neighbourhood of a pupil as the area within 3km of her home, and calculate the average difference in the academic performance of schools in the neighbourhood of poor and rich pupils. As we would expect, more affluent families tend to live in neighbourhoods with higher quality schools. We can also use the database to estimate an approximate proximity criterion, and to look at the schools that a particular pupil could reasonably expect to be admitted to. The difference in school “quality” is now much starker, over 50% higher in fact. This is the impact of the proximity rule, and operates over and above the simple fact that rich and poor live in different places.

This shows the mean academic quality of primary school attended (measured by the mean Keystage 2 score achieved in that school) available to high and low socio-economic status (SES) families in England. ‘Neighbourhood’ is defined simply as an area within 3km of the student’s house; ‘Catchment’ is defined as schools that the student would have a very high chance of getting into based on residential location and the school ’s catchment area. Standard error bars are displayed on the levels.

Clearly some criterion has to be used to resolve over-subscription. One possibility for use in cities is a lottery. But by its very nature, a lottery ensures that places are allocated in a way that ignores social background. All those families who have applied to an over-subscribed school are entered into a ballot, and as many names are drawn out as there are free places available (that is, once looked-after children, children with special educational needs, and siblings of current pupils have been assigned slots).

It is clear that lotteries are not a panacea and are not without difficulties, as our own research has shown. However, they do offer one potentially important way of raising social mobility.

We wait to see which way the new Admissions Code turns in the end.

Becky Allen reblogged this on Rebecca Allen.