What do you hope for in life? More specifically – and perhaps more mundanely – what did you hope for educationally? Were you always intent on going to university? Determined to leave school as soon as you could?

Students’ aspirations now feature in current education policy debates. This has formed an important part of the debate on social mobility. It is generally believed that having high aspirations is an important factor behind good performance in school. Whether it then follows that it is a good policy idea to attempt to raise students’ aspirations across the board is less obvious, but that is not the subject of this comment.

How are aspirations formed? Why do some students have higher aspirations than others? To make things concrete, one of the first big decisions that students have to make is whether to stay on at school at 16. Students continuing in school open up the possibility of university and a graduate career. Finishing education as soon as possible closes those possibilities down, at least in a straightforward way.

We can see a few straightforward patterns from a simple data analysis.

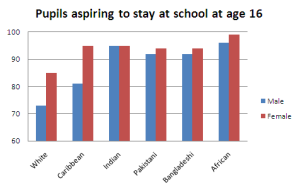

We studied responses to the question: ‘What do you want to do when you are 16?’ in the Next Steps dataset. The question was asked of 14 year olds in schools in England, and we focus on the simple distinction of whether they wanted to carry on at school or not. Figure 1 shows some simple raw means of educational aspirations by ethnicity and gender.

Figure 1: Percentages Aspiring to Stay at School at 16

The first point to note is that staying on at school is by far the most common aspiration for both male and female pupils across all ethnic groups.

Within this there are, however, huge differences between the different ethnic groups. For female pupils there is a ten point gap between White students at 85% and the South Asian and Black Caribbean groups at 94 or 95%. The proportion of Black African girls wanting to stay on at school is even higher, at 99%.

There is generally a similar pattern for male students across the ethnic groups. Again, over 90% of boys in the South Asian and Black African groups want to stay on, and again the proportion of White boys staying on is the lowest of all the ethnic groups at only 73%. Black Caribbean boys display a slightly higher proportion on average, at 81%.

It is interesting to briefly note that the aspirations of the respondents in this survey reflect actual activity at the age of 16 of a previous cohort: a higher percentage of students from Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Black African heritages stay on at school than do white British students.

Very similar large ethnic differences can be found in the students’ views regarding how likely it is that they will apply to university.

What influences this decision? Clearly, a full answer to this would involve a number of approaches including at least psychology and sociology as well as economics. Research evidence, including our own, suggests that the student’s prior attainment matters (the more able have higher aspirations), and that more broadly the students’ perceptions of their talent also matters; this is called “academic self-concept”. Some aspects of family circumstances matter, for example the qualifications of the students’ parents are correlated with their child’s aspirations, and some studies find that community or neighbourhood factors also matter.

However, the most important single factor is the aspirations of the student’s parents. Parental aspirations are a very strong correlate: 89% of students whose parents want them to stay on at school express the same wish.

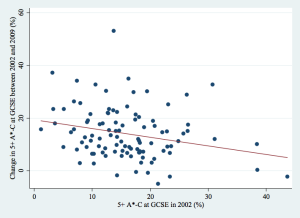

The overall average hides differences across ethnic groups, however. In Figure 2 we plot differences in parental aspirations and differences in the students’ aspirations conditional on their parents’ views for each ethnic group in our sample. The group percentages of parents wanting their children to stay on at school are displayed along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows the group percentages of students wanting to stay on specifically for the group of students whose parents also want this. The figure illustrates the great disparity in parental aspirations between White and Mixed White-Black Caribbean and the South Asian groups.

There are marked differences in parental aspirations across the groups: just under 60% of low-income White boys’ parents want their sons to stay on at school, compared to around 90% or over for Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Black African boys. There are high parental aspirations within these ethnic groups across the income distribution.

Figure 2: Student and Parent Aspirations

It seems that the passing on of high aspirations from parents to children is another dimension of the complex and multi-faceted transmission of opportunities and assets from one generation to the next.