Many countries struggle with a long tail of low attainment in schools. This blights individual lives and represents lost output for the economy as a whole. Low attainment is also typically associated with particular socio-economic backgrounds, and growing up in poor neighbourhoods, which strengthens the persistence of disadvantage. Increasingly, governments are turning to new ideas in an attempt to deal with this problem. One of these is the potential for incentives to change behaviours in schools.

Our new study shows that these have powerful positive effects on GCSE scores for many pupils wiping out about half of the disadvantage attainment gap in secondary schools. This effect is concentrated on low-attaining pupils, with no effect on high attainers.

Why are incentives needed? There is an obvious and substantial incentive for good performance in school – studying hard will earn good qualifications, which will bring a good income, better health, longer life expectancy, and higher self-reported well-being. For students who have already internalized the inherent incentives for working hard in school, additional rewards may add little further motivation.

But there are many places where that argument can break down for some pupils. Pupils may not really know what is needed to achieve high grades; they may misunderstand the importance of effort (rather than say innate ability or parental resources); they may believe that qualifications will not help them; they may lack the facilities to study and the motivation to secure them; or they may only really care about now. Such students may be responsive to short term incentives for effort. So it seems likely that there will be diverse responses to incentives: powerful for some, irrelevant for others who are already well motivated.

We set up a large scale field experiment involving over 10,000 pupils in 63 schools to test the impact of incentives. We recruited schools in the poorest decile of neighbourhoods in England. The experiment was funded by the Education Endowment Foundation, to whom we are very grateful.

We incentivised inputs (effort and engagement), not outputs such as test scores. These were repeated, immediate rewards incentivising effort and engagement at school. The pupils involved were in year 11, the final year of compulsory schooling leading up to the very high stakes GCSE assessments. The incentives are based on conduct in class, working well during class, completing homework, and not skipping school. We compared a cash incentive and a non-financial reward: a high-value event determined jointly by the school and students. The cash incentive offered up to £80 per half-term (for a total of £320 over the year). This might sound a lot, but at the youth minimum wage some of them would be earning a few months later, it works out at less than an extra hour per week-night. All the details are in our paper.

The experiment has yielded promising new results. In fact, our paper is the first to test the use of behaviour incentives for high-stakes tests, and the first to compare financial and non-financial rewards over the timescale of an academic year.

Behaviour was incentivised in classes for GCSE Maths, English, and Science. Our hope was that improved effort and engagement would raise GCSE scores, even though the scores themselves carried no rewards. The overall impact of the incentives on achievement is low, with small, positive but statistically insignificant effects on exam performance. However, that small effect is an average of the effect on two groups. There are pupils who “get” the inherent incentive in education, have no need of further encouragement and for whom we would expect zero effect; and there are pupils who don’t, and who might well be affected by a more immediate and obvious reward.

We use statistical techniques to identify these two groups using the rich data on pupils available in the National Pupil Database. In fact, at least half of the pupils have economically meaningful positive effects, principally but not only for the cash incentive. We find that this has very substantial and statistically significant effects in Maths and Science. In the metric researchers use to compare results across studies, the Maths GCSE score increased by 16% of a standard deviation (SD), and the Science score by 20% of an SD. Education researchers will know that these are very large effects. Another comparator is that this has equivalent effect to a very substantial improvement in teacher effectiveness (one SD).

The best way of gauging the impact of the intervention is that for this group it is more than half of the impact of poverty (eligibility for free school meals, FSM) through secondary schools . This is worth emphasising: a one-year intervention costing around £200 – £320 per student eliminates half of the FSM gap in Maths and Science GCSE scores in the poorest neighbourhoods.

Of course, to repeat, there are pupils for whom this intervention has no effect, pupils who are already putting in a huge effort at school.

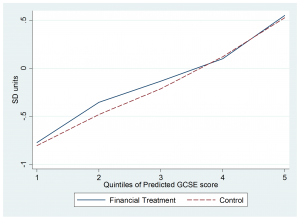

So who are these groups? The Figure below shows very clearly that the impact is on low attainers. The graph focusses on the effects of the cash incentive in Maths GCSE. Among pupils with low predicted GCSE scores, pupils in the intervention group scored substantially more than in the control group. That’s not true among pupils expected to do well, the incentive makes little difference. In this sense, this intervention is perfectly targeted: unlike other interventions the group getting the most out of it are the policy-focus low attainers, not those already doing well.

We also analysed the impact of the incentives on summary measures of GCSE performance, including passing the 5A*C(EM) threshold. For the low attainers, this increased significantly by around 10 percentage points, and not at all for the high attainers. This is important because of the very high earnings penalty to not reaching that benchmark, estimated at about 30% of earnings.

To summarise, we offered pupils incentives to raise their effort and engagement at school. This had very substantial effects on the Maths and Science GCSE performance of half of the pupils. This impact was high enough to wipe out half of the FSM attainment gap, and is concentrated on low attaining pupils. We ran the intervention as a randomised controlled trial for over 10,000 students in 63 schools in the poorest neighbourhoods of England. This seems to offer some very promising leads for schools and for policy makers. I’ll write more about that in my next post in a few days’ time.