Last week, on National Offer Day, families discovered which secondary school their child will be attending. There is one stark difference in the school choice process across areas in England: the number of school choices that parents are permitted to make. Many cities allow up to six choices, but there are cities that allow only three. We argue for reform to give all parents the same number of choices and therefore potential access to the “best” school for their child.

For many, the process leading up to National Offer Day has been complex – parents spend time reviewing their options, they fill in the preferences form online and then wait for the outcome several months later. The school offer to each family is determined by an algorithm that takes into account all choices by parents in their Local Authority, the number of places available at each school and school admissions criteria. There are good points and bad points about this system, and we have been among those calling for reforms.

But at the heart of this process is a very simple and stark unfairness: in some places, families can list six schools as their preferred choices, in other places, families can only list three. This matters a lot because only having three choices to make restricts parents’ options

The evidence suggests that giving parents the opportunity to make more choices of secondary school is likely to be beneficial. With more choice slots available, parents can make more ambitious first choices, nominating their truly preferred school(s). In places where fewer choices are allowed, parents may have an incentive to nominate “safety” schools instead i.e. ones where their child has a very high chance of being admitted.

We estimate that roughly a third of households in areas with a maximum of three school choices might be constrained in their choices. This is significantly higher in some areas (for example in Bristol, Liverpool and Middlesbrough, over half of parents use up all the choice slots they have). This will have an effect on the allocation of pupils to schools. It is likely to encourage parents to play “safe” and nominate their local school in which they stand a good chance of getting in. This works to preserve the neighbourhood segregation which school choice has the potential to alleviate. It also means that those “play it safe” schools have more of a captive audience and less pressure to raise their game.

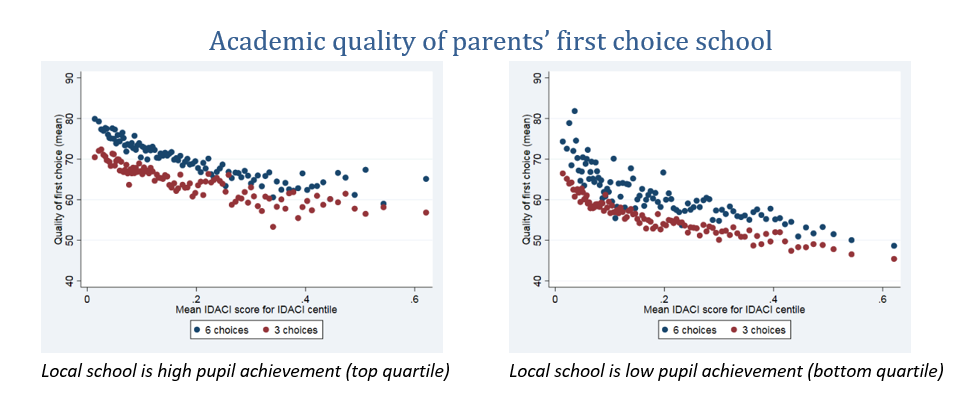

Having more choice slots available allows parents to be more ambitious with their top choices and still play safe with the lower choices. We can illustrate this point using data on parents’ secondary school choices in England from the 2014/5 cohort. The Figures show the average pupil achievement of first choice schools in Local Authorities (LAs) with six choices and in LAs with three, across the range of neighbourhood poverty. To account for differences in the choices available to parents (for example, London allows six choices, and of course also has high-performing schools), we draw the graph separately for parents whose local school is of high pupil achievement, and for those where it is of low pupil achievement.

This difference is evident in all areas, including areas with high levels of neighbourhood poverty and whatever the academic performance of the local school. This suggests that allowing more choices would improve the outcomes for parents. This is likely to lead to more pupils being assigned to a school of their choice, rather than their “safe” school. Our evidence clearly shows that first choices are more ambitious in terms of a measure of school pupil achievement in LAs where parents can make six choices rather than just three.

The thought experiment for this proposal is as follows: imagine an LA with three choices available that increases to allowing six choices. Parents respond by making more ambitious choices in their top choice slots. At the date of the policy change, the number of places in high-performing schools, low-performing and so on are all fixed; the issue is about allocation, which pupil ends up at which school. We conjecture that the impact on school attended is likely to be greater for pupils from poorer neighbourhoods. For more affluent pupils, there may not be much further gain available; but for poorer families, a more ambitious first choice might bring them into consideration for substantially higher performing schools.

What are the costs of this reform? The websites that are dedicated to school admissions would have to be updated to include more school choices if the permitted number was increased to six. For most websites, the only cost would be once-off and minimal. There are some aspects of the school choice process that are still paper-based (for example supplementary information forms), which would cost more with more choices made, but this is not a significant component of overall costs. The cost for parents should also be small: some additional time might be taken to complete the application process. There would arguably be more time taken to research schools, but this research may have been conducted anyway, before selecting three choices rather than four or more. In any case, parents are not forced to make the maximum number of choices.For LAs, if increasing the number of choices led to an increase in the number of cross-LA school choices, this may increase the co-ordination required between LAs.

Overall, we see this as a very simple reform to improve the fairness of the school admissions process that has important benefits and small costs. Having only three choices, or even six, is low compared to elsewhere in the world: for example, Spain allows eight choices and New York City allows twelve choices. We propose that Local Authorities (LAs) be encouraged or required to increase the permitted number of school choices that parents can make.

Simon Burgess, Estelle Cantillon, Ellen Greaves, Anna Vignoles